- Home

- Dan Rhodes

Little Hands Clapping Page 8

Little Hands Clapping Read online

Page 8

Nobody ever railed on their deathbed that It was the doctor – he should have seen the warning signs. No grieving husband or wife ever came after him with a team of lawyers. Instead they sighed, and said he had done everything he could. When the television cameras arrive his patients will queue up to say just how dependable he had appeared to be, and how capable and kind, and how the news had come as such a shock.

He sat behind his desk and waited for his first patient of the afternoon, a Frau Irmgard Klopstock, one of the many middle-aged women on his books. As she sat down she started talking, red-faced, about how pleasant the weather had been, and how her garden had really come to life. Once this was over the doctor asked her why she had come to see him, and she told him how ashamed she felt for having troubled him, because the pain she had been feeling had gone away. ‘It is as if just being here in your consulting room has cured me,’ she said.

He had noticed something awkward about the way she walked in, and decided to press her. ‘Tell me anyway,’ he said, ‘before it went away, where was this pain?’

Frau Klopstock turned an even brighter red, and he gave her his gentle You can tell me, I’m a doctor look. In a trembling whisper, she told him. He smiled. She was relieved that he had pressed her, that she had finally told somebody other than her husband about this problem. She felt a weight lift from her shoulders, and was thankful for having such a wonderful family doctor.

He reached into his desk drawer for his camera. ‘Now,’ he said, reassuringly, ‘for medical purposes I am going to take a few photographs of the affected area. Frau Klopstock, please would you remove your . . .’ He gestured.

She did as he asked.

Doctor Fröhlicher smiled. With the new addition to his freezer the day had started well, and it kept getting better.

VII

As he worked, the skeleton expert was grateful for the black curtain that surrounded him, because it stopped him from having to see the Harsh Realities room’s other exhibits every time he looked up from his work. To one side was a papier-mâché dummy of a woman in a bath, the water made from red Cellophane and her mouth hanging open as her eyes bulged and her sky blue head rolled backwards, and to the other side hung a series of photographs, blown up and mounted on canvas, of the shattered body of a Seoul stockbroker who, on seeing some unfortunate numbers appear on a screen, had hurled himself from a very high window. He was glad that this job would only last for one day.

The skeleton expert heard few footsteps. He was not surprised. He had no idea why anybody would want to visit a place like this.

As the museum closed for the day, Hulda returned to make sure the area around the new exhibit was left clean. She made two cups of coffee and took them to Room Seven. She pulled aside the black cotton, and as the coffee cooled she watched the skeleton expert attach the feet. She tried to let him do his job in peace, but it was impossible. Only by speaking, or singing, or humming, could she keep her most horrifying memories and her most petrifying visions of the future at bay. She could feel them creeping up on her, and urgently needing to fill the silence, she asked the skeleton expert all the questions he had come to expect from such encounters. As he gave his customary replies she found herself becoming fascinated, and in her subsequent questions she delved a little deeper, asking how the bones were prepared. He told her all about the ammonia, and the beetle larvae. After a few more technical questions, Hulda asked about the bones’ history.

He worked on as he told her what little he had learned from the skeleton’s executors. It had all been quite straightforward. Before he died, the skeleton had given a reason for his decision, one which people had been ready to accept: there had been a woman who had decided she didn’t want him after all, and he had believed he couldn’t live without her. The case could have come from a textbook, the only deviation being his request for his bones to be preserved.

Hulda noticed that, like all skeletons, it seemed happy. Inside all of us, she reflected, were smiling bones. She would do her best to remember from now on that even on the hardest days there was always a smile underneath her skin. She made a mental note to report this thought to Pavarotti’s wife, to let her know that the new exhibit had already brought inspiration to a troubled soul.

She still wished with all her heart that the skeleton had held on and waited for things to get better. She had held on. It had been hard, at times excruciating, but she was glad she had. Silence descended, and as steam rose from the coffee, she felt as if she and the skeleton expert were exchanging sad stories around a camp fire, and that it was now her turn to take the floor. She started telling him about her stepfather, and as her story went on he found he could no longer concentrate on his work. He put his tools aside, picked up his mug and listened in horror.

She didn’t tell him everything, not by a long way, but she gave him a flavour of what her life had been like for those years, how it had felt for her to be woken by the scratch of a moustache and a blast of breath that smelled of beer and pickled onions. She told the skeleton expert that at the end of one particularly awful night, when her stepfather had at last left her alone, she had cursed God for having allowed such things to happen to her. ‘You should have heard some of the names I called Him,’ she said, her face grave. ‘I shock myself just thinking about it, but at the time I was very angry, and I didn’t know who else to blame. The Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, well, I am afraid all three of them came in for quite a scolding.’

Although such an outburst had only happened once, she knew that had been enough. She had committed the only unforgivable sin, and from that moment, no matter how she lived the rest of her life and no matter how much she prayed for salvation, she was destined to spend eternity in the fires of Hell. ‘I can’t even say that I didn’t really mean it,’ she said, ‘because I meant it with all my heart. It’s a pity that God can’t forgive me, but I do understand that rules are rules.’

The skeleton expert had no idea what to say. He wondered whether he should tell her she was wrong, that when she died she would not go to Hell because there was no such place, and there was nothing awaiting her. He stopped himself. He didn’t want to disparage her faith, and besides, he only hoped he was right. It was so much easier to think that there was nothing waiting for him than it was to face the alternative.

‘Please do not make this mistake,’ she said.

He could see how much this meant to her so he nodded, but it was too late. Without even thinking about it he had said such unholy things more times than he could remember, and if any of this was true he was in serious trouble. He tried not to think about it as he drank the last of his coffee, thanked her for it and went back to his tools. He was relieved when she took the empty mugs and stood up, but she had not finished.

‘But of course,’ she said, ‘it is important for me to remind myself that I must not end up as this poor gentleman has, that I must do all I can to stay alive for as long as possible. Otherwise what would I be doing but playing straight into the Devil’s hands?’

The skeleton expert said nothing, and Hulda, her brow furrowed and her head bowed, went away.

At seven o’clock Pavarotti, Hulda, Pavarotti’s wife and the old man stood in a row, waiting for the skeleton expert to make his final adjustments. After some almost invisible changes with some very small tools, he straightened up and stepped aside.

Pavarotti’s wife was the first to examine the new addition to the museum. She looked the bones up and down, and spoke the words she had prepared.

‘Friend,’ she said, ‘in death you shall be of service to others. Through you they will see what a terrible mistake they would be making if they were to follow the same path.’ She reached into her enormous bag and pulled out a display card on a stand. At the top was the dead man’s name, and underneath, in four languages, was a single-sentence summary of his history. He had been heartbroken, it said, and seeing no hope of happiness he had hanged himself. There was a pictorial invitation to examine the crack in his ver

tebra, and in the bottom corner of the card was a photograph, provided by the man’s relatives, of him in happier times.

The room was silent but for Hulda’s sobs. She was heartbroken for the skeleton, but also angry with him for having done what he had done. Looking at the photograph she could see at once that she could have loved him, but now it was too late. He had chosen to die rather than find her and spend his life with her. Her sobs were fuelled by a swell of self-pity, and the shame that came with it. Pavarotti’s wife put a hand on her shoulder.

Slowly Hulda pulled herself together. As the world around her came back into focus she saw that Pavarotti was looking directly at her, his eyes full of concern. Her heart sped up, and she wondered whether this would be a good time to ask him if he had a brother. Before she had a chance, his wife started speaking to the skeleton again, and the moment was gone.

VIII

Hans looked up at his master with expectant eyes. Two thick steaks overlapped on the plate, and the doctor was already thinking about frying a third for dessert. He cut off a fatty chunk, and threw it high. Hans leapt up and caught it, and the doctor, his cheeks round with meat, explained that with the new addition to the freezer they could allow themselves a little overindulgence as they finished what remained of the woman they had been eating for such a long time. He always got as much use from each body as he could, and as he refined his butchery techniques less and less went to waste, but there were still a few parts he would never eat. Armpits repulsed him and went straight into the bin, and the thought of putting another man’s penis in his mouth, no matter how well-disguised by sauce, made him shudder. He had no qualms about feeding male genitalia to Hans, though. He had known effeminate dogs, and hoped the testosterone would help ensure he never went down that route.

Sitting beside the steak was something he had been saving: one of the woman’s kidneys. He sliced into it, and could taste it before it had even reached his mouth. As always, it reminded him of the first time.

Doctor Fröhlicher had started eating people in his first year at the hospital. At a particularly messy post mortem he had, without asking himself why, slipped a kidney into his pocket. When he got home the apartment was empty. Ute and Hans were out on one of their walks, and straight away he cut it into slices, fried it, and put it on a plate alongside a chunk of bread and a spoonful of his favourite mustard. It had tasted much like any kidney he could have bought from a butcher’s shop, the only difference being that it was much, much better. The feeling that surged through his body reminded him of the moment his hands had first cupped Ute’s breasts. Just like that time, as soon as it was over he could think of nothing but how he could find this feeling again. While he had been preparing the meat he had told himself that he was doing this only out of idle curiosity, that all doctors must try it at one time or another, but as soon as the food was in his mouth he knew why he had really done it, and he knew that it had worked. As he chewed, he no longer wondered where his wife was, or what she might be doing. The meat had given him a respite from the nagging pain of his desperate love, but once it had been swallowed and the taste had faded, all the usual fears rose up before him once again, and he struggled to drive them away.

From that day he would take every opportunity to pocket an off cut from an autopsy, or furtively slice a wedge from an amputated limb. When Ute was gone the nature of his pain changed but he found he needed this relief more than ever, and as his hunger intensified he brought home more and more. With this habit came the worry that at any moment he might be discovered, and lose his licence, and no longer be able to cure people, and sometimes fear and a burning shame took over and he would look Hans in the eye and vow to stop. In the moment he meant this absolutely, but as soon as the next opportunity presented itself the vow would be forgotten.

One afternoon a nurse had come close to catching him as he hid a liver in his briefcase, and in that moment he could see what he was doing. He was losing control of himself, and he knew he had to put this behind him. He decided that the only solution would be to remove himself from the temptations of the hospital. He moved into general practice, hoping that his daily duties would keep him detached from any possibility of a relapse, and for years this worked. His shame receded, but the agony remained, and with it the knowledge that all he would ever need to give himself a respite from it would be a mouthful of illicit meat.

One morning the phone rang, and the doctor went to the museum to attend to a girl that the old man had found in Room Six, moaning as she lay next to a puddle of vomit, an empty bottle of aspirin by her side.

Doctor Fröhlicher had been Pavarotti’s wife’s family doctor since he had moved to the city. She considered him to be the museum’s doctor too, and had given the old man his home and work numbers, telling him to call straight away should he or any visitor ever need medical assistance.

That day he had crouched over the woman, and listened to her heart with his stethoscope. He gave her a glass of water and made sure she drank it all before sending her on her way, his mind racing the whole time. When she was gone he explained to the old man that he would not fill in any paperwork, that to do so would draw attention to this episode and might damage the reputation of the museum.

‘For the sake of the nerves of the proprietress,’ he said, ‘I think it would be best if you were always to call me in the first instance, even if the prospective patient appears to be in an advanced state of . . . no longer being alive. There will be no need for an ambulance, or any of that silliness. We are both gentlemen of the world, so let us keep such incidents between ourselves.’ He looked hard at the old man, and had a feeling that they understood one another. He smiled, and said, ‘Until the grave.’

The old man nodded. He had no interest in telling anybody about what had happened. He just wanted to clear up the mess in Room Six, and forget the incident had ever occurred.

The doctor went away, his heart racing. He felt torn in two, one part hoping that he would never hear from the old man again, and the other almost feverish with anticipation. Three weeks later his telephone woke him once again, and the moment he heard the familiar voice he knew what had happened, and he knew what he would do.

He struggled to avoid showing the old man how much he was trembling as he was invited in through the back door. This time he could tell at a glance that the person he had rushed over to treat was quite dead, and it was the same the next time, and the next.

The old man could see that the doctor was acting unconventionally, but he had no cause for concern. All that mattered to him was that his own hands were clean, and he had fulfilled his duty by contacting a medical professional. If that medical professional then chose to bundle the body into the back of his car and drive away at high speed it was hardly his concern. He wasn’t going to tell a doctor how to do his job.

Carefully categorised receipts found by the police in a filing cabinet at the doctor’s home will reveal that around this time he had made a visit to a kitchen goods store, where he had bought a second chest freezer, a large refrigerator and a selection of steel hooks.

With two complete bodies in the garage, Doctor Fröhlicher could see weeks, even months, ahead, and just knowing that at any time he could go to the fridge and cook some meat was enough to keep the torment at arm’s length. Feeling how different life could be with a regular supply, he had grown determined never to go without again. He felt sad for these people, though. Had they walked into his clinic he would have done everything in his power to help them, but they had not; by the time they came into his life each one of them had made their final decision, and it was too late for him to help them. He was sure, though, that they would all have been happy to know that even though they were gone, they were still helping him, a general practitioner, to get through the day.

There had been times when his reserves had run low and he could feel unrelieved despair hovering close at hand, but he wasn’t going to worry about that now. The old man would call again before the freezer was empty. H

e always did. The doctor told himself that everything would be fine, that somewhere in the world there would be somebody so unhappy that they could see no light, and somehow they would find their way to the museum, where they would crumble in defeat.

IX

Mauro and Madalena said goodbye to their families and began the long journey to the city, Madalena with dreams of becoming a pharmacist, and Mauro planning to qualify as an optician. They had spoken of one day returning to the town and opening businesses directly opposite one another, so in quiet moments they could look at one another across the street, and smile. But that was something to think about another time. For now they were too busy trying to hide their nerves as the bus took them away from everything they had known. After just a few minutes it all seemed a world away: the town square, the shops and the faces that had been there all their lives, growing older but somehow remaining just the same. As the bus carried on, down and down, they looked out of the window, their fingers intertwined. They said very little, each of them hoping they weren’t making a mistake.

Their days filled with campus maps, classes and long sessions in libraries, but every evening, when their studies were over, they met up and explored, getting lost in mazes of narrow streets, embracing on bridges, sitting on the steps of grand buildings, looking out for dropped coins and making wishes as they threw them in fountains. They sought out places that sold cheap coffee, and drank it slowly. They were happy just to be together, to do whatever they felt like doing without the thought that their every movement was being monitored by neighbours, aunts and shopkeepers. As the city thundered around them they had never felt so invisible, and their evenings would always end in one of their rooms, their bodies wound together on a single bed as they spent the long hours they had been dreaming of, their kisses slow and their fingers following hitherto unexplored contours on each other’s skin.

Little Hands Clapping

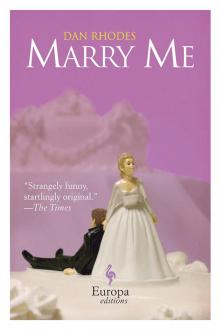

Little Hands Clapping Marry Me

Marry Me This is Life

This is Life